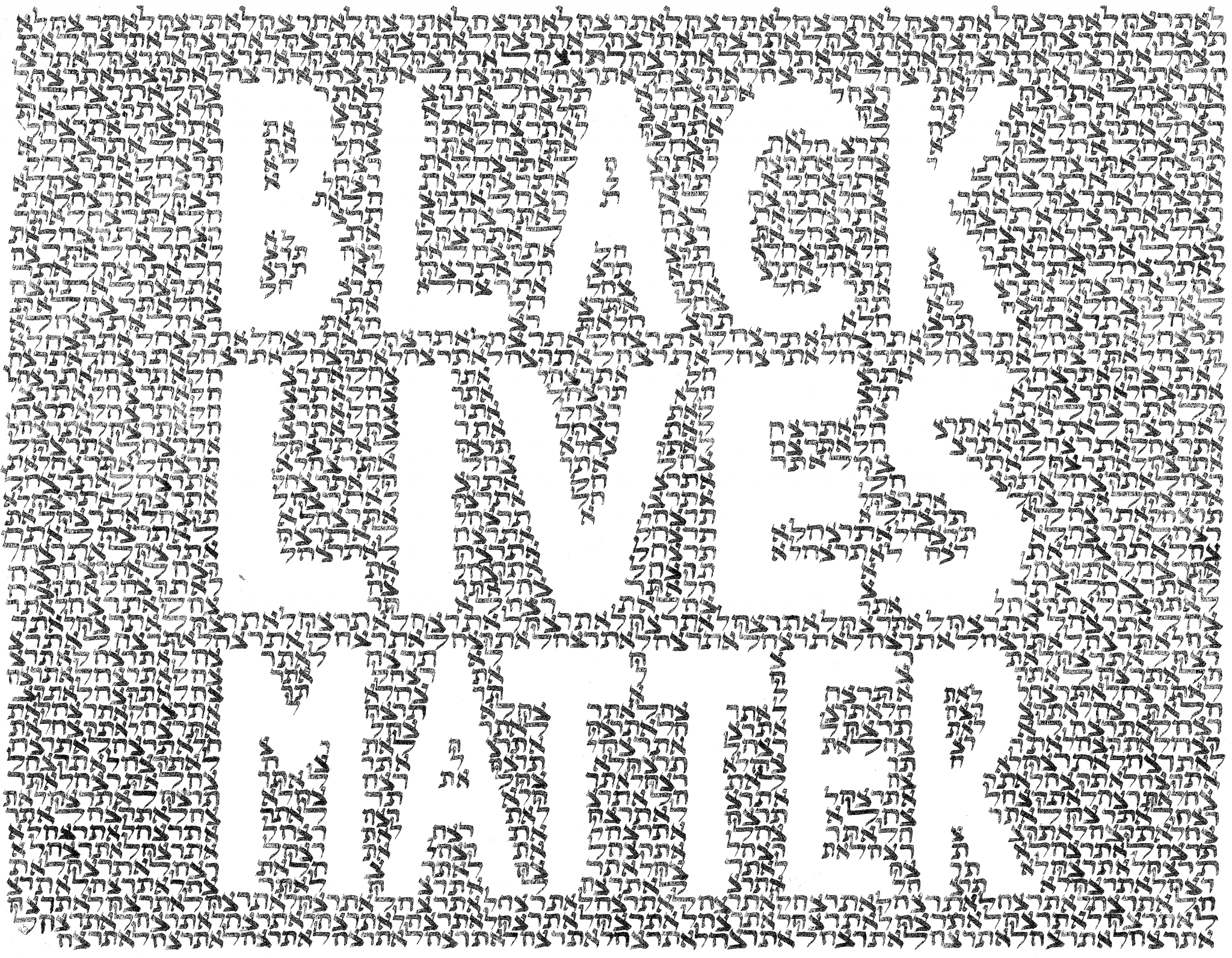

(Lo Tirtzach/Thou Shalt Not Murder art by Rachel Stone)

Rosh Hashanah, II Tishrei, 5781

Long, long ago, in the days before COVID, we used to do things like see movies in crowded theaters.

A few years ago, I went with my family to see a movie. I don’t remember which one it was, but it must have been a recent release because the theater was packed. I remember it was winter time, because we were all doing that thing that you do with coats in a theater – no one wants to either put their coat on the floor, or hold it through the entire movie, so everybody designated a seat in their row as “the coat seat.” If you looked up and down the rows, you would see every few people, a seat buried in mountain of coats and scarves.

Now, the seat next to me was someone else’s coat seat for awhile. I think.

As the theater filled up, the ushers asked us to move our coats, and to raise our hands if we had an empty seat next to us. In my peripheral vision, the shape next to me was a coat mountain. So I raised my hand. And then I heard a voice that made me turn, and I saw that there was next to me, not a pile of coats, but a person. A black woman. I remember being flooded with embarrassment and shame at realizing that I had somehow neglected to even be aware of the presence of a human being sitting a foot away from me. I didn’t even see her. I of course apologized immediately, but I spent the entire movie wondering how that could have happened.

I have revisited that incident over the years. Could you explain this as an honest mistake? It was dark. There were all the coats. There had been a pile of coats next to me for awhile, hadn’t there? I couldn’t be certain. But what I was certain of were the woman’s eyes, when I finally turned and saw that she was there. I can’t forget her eyes. Something about the way she looked at me told me this wasn’t the first time she had been invisible to a white person. And I know my experience, my not-seeing, is part of a much bigger problem.

I can’t go back in time and do it over again. But I am doing my utmost to really see the people around me, and to make sure something like this doesn’t happen again.

When we don’t see people, we dehumanize them. We disregard them. And the consequences of that cumulative disregard can be deadly.

Over the summer, since the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, there has been a greater reckoning the realities of race in this country. George’s death was not the first or last of its kind, but it occurred at a time when many more of us in this country were primed to take notice. With the stresses caused by the pandemic, George’s death was like lighting a match and throwing it on a haystack.

Some of us had already been in a process of examining our own relationships to race and our understanding of racism in our country. For others of us, the protests sparked have caused us to ask questions that we haven’t asked before about the nature of American society and our relationship to inequality. And there may be others among us who are feeling distressed and angry, as we watch some protests turn into looting and violent confrontations with the police. We may be experiencing a mixture of these feelings at one time.

These are not easy questions to grapple with. We want to live in a country where anyone can succeed with hard work. We want to believe that the past is in the past, that old wounds have been healed. The recognition that our society does not treat all people as created equal and give us equal opportunities can shake our core beliefs about ourselves, about our successes, and about the world we live in. And so we protect ourselves from the horror of knowing and the responsibility to act.

It is incredibly painful to confront the idea that, perhaps unwittingly, we may have participated in actions that have caused others harm or benefited from privileges that have been denied to others. I want to acknowledge that feeling.

Our identity as Jews adds an additional layer of complexity. We are keenly aware of the ways we have been othered, how the calculus of race has been turned against Jews. But the existence of Jews as a minority in this country and the fact Jewish oppression throughout our history can get in the way of our reckoning with the realities of race today. We can distance ourselves from responsibility for slavery and Jim Crow because most of our ancestors were not directly involved or may not have even been in the country yet, and because the same hate groups that have terrorized black people in this country are also deeply anti-Semitic.

And yet, in the recent history of our country, many Jews have been extended some of the privileges of whiteness that were once denied. In any social hierarchy, it is clear that if given the choice, most people would choose to be near the top. In a caste system, as historian Isabel Wilkerson describes it, that places whiteness and the top and blackness at the bottom, we all know on some level that proximity to whiteness improves our chances of safety, security, and success.

We are all shaped by the societies that we live in, and our society inculcates a certain set of beliefs and norms around race. Quite frankly, it would be more surprising for someone who has lived a significant portion of his or her life in this country *not* to hold racial biases on some level.

Those biases cause harm not only in the most virulent forms – the people in white hoods, the crowds jeering as black children try to enter a school. It also exercises itself in more subtle ways, ways we are not consciously aware of. Consciously, condemn discrimination in all forms. I actively seek out stories and perspectives different from my own. I have been taught, officially, about the dangers of prejudice. And yet, what happens when I really start paying attention to my gut reactions? Not my mind, not my heart – that part of me that has learned the unofficial lessons of living within a racial caste system:

That initial pang of anxiety at seeing a young black man approaching on the street, the internal voice that whispers “danger”.

The times when I have, without intending it, disregarded or been completely unaware of the presence of someone who was black.

It is in little burst of surprise at seeing a black or brown person in a position of power – at the head of the university classroom, or the doctor’s office, or the Oval Office. Even if it is pleasant. Even if we pat ourselves on the back for being so open-minded because our dentist is black, or our favorite college professor is black.

Now, my mind immediately jumps in and overrides my gut. But I would be lying if I pretended that the initial reaction wasn’t there. I am working hard to undo those patterns, but it takes time and effort to unlearn a lifetime of training, that is all the harder to work against because it is usually unspoken.

These may seem like small things, but they add up. As the number of people of color who end up dead after encounters with the police can tell us, unexamined biases can have serious consequences. We may not be personally at fault. But we are responsible.

To recognize our biases and to unravel them is an ongoing process rather than a single moment of realization. It is something that one must actively work toward, to root out the stumbling blocks and carve new mental pathways.

In this season of Teshuva, we are called to engage in precisely this type of reflection and discernment. To look honestly at ourselves and our communities and to ask deeply: where have we fallen short? To search and discover within our own hearts things we didn’t know were there, the parts that don’t often see the light of day. And then to ask: what can I do to make it right?

Teshuva is a multi-stage process:

- Becoming aware – Recognize what we’ve done wrong – without that, there is no teshuva

- Actually experience remorse or regret, and desire to make it right.

- Ask forgiveness of the person that you have wronged

- Do what needs to be done to make it right, to the extent possible

We have to begin somewhere, and the first step in this process is often the hardest. I am inviting all of us to participate in some study and reflection today to begin a conversation about race and what a process of teshuva could look like. You might not agree with all of the perspectives offered here. They are meant to challenge and to prompt us to ask questions. What I ask is that we approach this with open minds and hearts, with curiosity.

Here’s how it will work: The texts for study are included in the packets that you may have picked up in person. A digital copy was also sent out via email and posted to the KH website. I will introduce the texts in two sections, with some guiding thoughts or questions. Then, either individually or with others, we will take a few minutes to read and consider them. We will come back together and I will introduce the next set and repeat the process. At the end, we’ll join back together for some concluding reflections.

The first two texts, from Michelle Alexander and the Rev. Anthony A Johnson are focused on the first stage of teshuva – cultivating awareness.

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow, 2010

Much has been written about the ways in which people manage to deny, even to themselves, that extraordinary atrocities, racial oppression, and other forms of human suffering have occurred or are occurring. Criminologist Stanley Cohen wrote perhaps the most important book on the subject, States of Denial. The book examines how individuals and institutions – victims, perpetrators, and bystanders – know about yet deny the occurrence of oppressive acts. They see only what they want to see and wear blinders to avoid seeing the rest. This has been true about slavery, genocide, torture, and every form of systemic oppression.

Cohen emphasizes that denial, though deplorable, is complicated. It is not simply a matter of refusing to acknowledge an obvious, though uncomfortable, truth. Many people “know” and “not-know” the truth about human suffering at the same time. In his words, “Denial may be neither a matter of telling the truth nor intentionally telling a lie. There seem to be states of mind, or even whole cultures, in which we know and don’t know at the same time.”

Questions for reflection or discussion:

- Do you relate to the idea of “knowing” and “not-knowing” at the same time?

- What steps can you take to consciously “know”?

2. Rev. Anthony A. Johnson, June 3, 2020, Atlanta Jewish Times

Those of us who seek to once again re-establish black-Jewish relations in Atlanta have to learn how to prioritize one another’s efforts. And in order for our respective cultures to understand one another’s needs, there must first be “real” dialogue, real understanding. Understand that each and every day, every one of your black friends in Atlanta and across America, including me, lives with the reality of being killed by police officers. Many Jews are passing as white. Black Atlantans need you to be proud kippah-wearing Jews and stop passing as white (to those who it applies to) and experience the “inconvenience” of being people of color (which is what you are) even if you’re Ashkenazi. My black is beautiful. And YOUR black is beautiful.

Atlanta, we know that there is power in numbers. The truthful acknowledgment of Jews in Atlanta, throughout the Southeast and around the world as people of color will not only allow you to be your authentic selves, a proud people who protested and subsequently defeated Pharaoh of the Torah/Old Testament, but it will cause a deep, transformational change in your hearts toward your black brothers and sisters, understanding the plight of blacks in white Atlanta and white America feeling with “empathy” versus “sympathy” because we have the same Pharaoh in common.

Questions for reflection or discussion:

- What do you make of Rev. Johnson’s assertion that Jews are “passing” as white?

- Is identification with the Black experience necessary for a commitment to pursuing racial justice?

The idea of simultaneously knowing/not-knowing captures why it is often so hard to accept what the evidence suggests to us. I would argue, as I mentioned earlier, that not-knowing is a protective stance – a way to cope with the painful reality. The horror of fully knowing may be painful to bear and lead us to feel guilty.

Johnson also talks about knowledge, specifically in the relationship to Jews and racial justice. He makes a number of claims that are somewhat provocative and that you may or may not agree with, but for Johnson, full knowing of our identity as Jews can lead to a deeper empathy with the struggle of other people for justice and equality.

The following two texts, from Maimonides and Rabbi Jason Rubenstein, deal with the next stages in the process of teshuva – repairing the harm and seeking forgiveness.

3. Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Laws of Teshuva 2:9

Neither repentance nor the Day of Atonement atone for any save for sins committed between a person and God, for instance, one who ate forbidden food, or had forbidden sexual relations and the like; but sins between a person and his or her fellow, for instance, one injures his neighbor, or curses his neighbor or plunders him, or offends him in like matters, is not absolved unless he makes restitution of what he owes and begs the forgiveness of his neighbor. And, although he makes restitution of the monetary debt, he is obliged to pacify him and to beg his forgiveness. Even if he offended his neighbor only in words, he is obliged to appease him and implore him till he is forgiven by him. If his neighbor does not want to forgive him, he should bring a committee of three friends to implore and ask of him; if the neighbor is not convinced by them, he (the offender) should bring a second, even a third committee. If he still does not want (to forgive) he may leave him to himself and pass on, for the sin then rests on the one who refuses forgiveness. But if it happened to be his master, he should go and come to him for forgiveness even a thousand times till he does forgive him.

4. Rabbi Jason Rubenstein, “In Jewish Tradition, Racism is a Sin,” Forward, June 8, 2020

Repentance is not a private act carried out between a sinner and God, nor is it completed when the sinner has mended his ways. Rather, according to Rabbi Isaac Hutner, one of the 20th century’s most intriguing rabbinic thinkers, repentance means a basic rededication of one’s life to discovering and rectifying the cascading ways that a single act of violence has transformed and broken the lives of others, and therefore the world:

“As long as the destructive effects of a sin remain in the world, a penitent is obligated to repair them, so that the evil and brokenness of the sin remain only in the past. Just as abandoning the sin prevents the sin itself henceforth, so too the repairing of what is broken cuts off the branches of the sin that reach into the future.”

The consequences of our actions race ahead of us, into the future: when a car is wrongfully impounded, a parent can no longer commute to her job, a family is evicted, children lose access to school (and with it, lunch), carrying trauma and missed developmental milestones into their adult lives. Repentance is the act of cauterizing the future against the rupture that metastasizes from the sins of the past. It is important to reform the policies by which vehicles are seized, but it is not repentance: repentance is mending the physical and psychological scars left on those whose lives were upended by the old policy. This isn’t always possible; this potentially-tragic aspect makes repentance an example of what philosophers call a ‘regulative ideal,’ one towards which we must strive even though we will never attain it, like complete fairness or perfect rationality.

Past sins are never confined to the past, but are always woven into the very fabric of the present. This is why we must, as Coates put it, consciously exert an opposite force. Repentance means not only admitting that past actions were wrong, but also reckoning with the fact that, because of those actions, the current state of the world is wrong as well.

____________________

In his code of Jewish law, Maimonides describes both the need to both make restitution- to repair the damage done – and to actively seek forgiveness from the one who was harmed. As Rabbi Rubenstein describes, drawing on the work of Rabbi Hutner, Teshuva involves a continuous process of seeking to repair the effects of the sin. It reframes our approach to life- we cannot be satisfied by a single action and conclude that we have fulfilled our responsibility. This suggests that we need to concern ourselves not only with root causes but also with the effects that radiate out from past harms.

I know this was not enough time to give each text a fair treatment. My hope is that the opportunity to learn together helps us to open our hearts and look inside ourselves. Even if we think we know ourselves inside and out, the reality is that we are all complex.

In one of the prayers we sang together earlier this morning, we describe God as one who bochen levavot – examines our hearts, goleh amukot – reveals our depths; yodea machshavot- knows our thoughts and tzofeh nistarot – uncovers mysteries. God as described here knows everything about us – even the things we may not yet know about ourselves. These images might parallel our own process of reflection. We might also feel that we are digging into our depths, or discovering mysteries. We might encounter resistance, too, or parts of ourselves that are just too tender to touch. That is also a part of the process.

Being honest with ourselves is hard work, but we don’t have to do it alone. In our tradition, the process of teshuva is not only individual, but communal. We take on responsibility for the things that everyone in our community has done, knowingly or unknowingly, we hold one another accountable, and we lean on each other for support. We’re in this together. We don’t have to achieve perfection or have it all figured out by the end of Yom Kippur. The hardest part is just to begin.

To paraphrase the words of Rabbi Tarfon in Pirkei Avot, “It is not upon us to complete the work, but neither are we free to desist from it.”

I’ll conclude with the words of James Baldwin:

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”